Issue 25, winter/spring 2018

https://doi.org/10.70090/GW18PPMP

Abstract

This article discusses the mediated presentation of the Nakba in the post-Oslo era through an examination of ‘anniversarial’ journalism. By viewing media as an interpretative memory community, this work reveals how Palestinian society has shaped its ideological framing and worldview over time. Building on previous scholarly works which challenge media’s preoccupation with the immediate present, this work highlights the mediated application of the past in Palestinian media as a prospective memory that reflects the communities’ political and cultural circumstances in line with the disparate historical and contemporary geo-political circumstances in East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and inside the 1948 borders. This article opines that within these communities the Nakba is not simply invoked as a foundational historical event, but as an analogy which contextualizes present-day cultural and political concerns as a result of the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Introduction

With the seventieth anniversary of the official outbreak of the war[1] in Palestine fast-approaching, this article discusses the mediated presentation of the Nakba in the post-Oslo era.[2] Palestinian newspapers, both print and online, have been examined in the period between May 1994 and May 2016. The newspapers with the largest readership and circulation in East Jerusalem, the West Bank and inside the 1948 borders, respectively Al-Quds [Ar. Jerusalem] and Kul al-Arab [Ar. all the Arabs], were selected. Complemented by an analysis of al-Hayat al-Jadida [Ar. the new life], the official daily newspaper of the Palestinian National Authority (PNA or PA) established in 1995, the examination of the most influential Palestinian media in the post-Oslo era[3] reveals how Palestinian society has shaped its ideological framing and worldview over time, illuminating the workings of media as well as providing valuable insight into a society’s self-understanding.[4]

Indeed, the media, as with other ‘interpretative memory communities,’ disseminate “mediated memories”[5] that fall within a cultural and political framework dictated by the interests of media’s audiences and financial patrons.[6] Even though (individual) media producers are responsible for the creation of culturally resonant narratives as “creators of meaning,”[7] the necessary dialogic interaction between journalists and audiences blurs the line between the media producer and the consumer, creating what David Lowenthal calls “a unifying web of retrospection.”[8] Media professionals, as “the people behind the text,” consequently are not be considered here as creators of novel mnemonic interpretations, but rather constructors of cultural-interpretive media frames that reflect the Palestinian communities’ Zeitgeist.[9]

Building on previous scholarly works challenging media’s preoccupation with the immediate present,[10] this article highlights the mediated application of the past in Palestinian media as a ‘prospective memory’. The concept of prospective memory, as defined by Keren Tenenboim-Weinblatt, conceives of mediated memories as vehicles that spur on a ‘to-do-list’ and encourage the execution of an intended, prospective action.[11] As will become clear through a systematic analysis of ‘anniversarial’ mediation—media output pertaining to Nakba Day mnemonics—the Nakba is not simply invoked as a foundational historical event, but as an analogy which contextualizes and legitimizes present-day cultural and political concerns resulting from the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

While recognizing that the Oslo Accords on both sides of the Green Line transformed the media into a ‘counterhegemonic public space’ for and by Palestinians,[12] this work illustrates that the disparate historic and contemporary political landscapes on both sides of the Green Line have resulted in divergent “national problems” or “nationalist goals”.[13] Through the inclusion of news outlets that represent different Palestinian communities, this article differentiates between media production in Palestinian society on both sides of the Green Line[14] and reveals that post-1994 Palestinian media mirrors Palestinian communities’ particularistic engagement with Israeli hegemony. An historical analysis of media content pertaining to Yawm al-Nakbah [Ar. Nakba Day] and the associated Nakba mnemonics over a period of twenty-two years demonstrates that Nakba media output primarily constitutes an interpretative framework for contemporary grievances held by the Palestinian minority inside the 1948 borders, which since 2011 include legalized efforts by the Israeli majority to thwart Nakba commemoration. Within the same period, the Nakba has been employed as an all-encompassing metaphor in the West Bank and East Jerusalem. Representative of the Nakba as a ‘present continuous’, mediated Nakba output here intertwines the undoing of the Nakba based on the ‘right of return’ [Ar. haq al-ʻawdah] and national independence through the establishment of a Palestinian state with East Jerusalem as its capital.

Laying the Groundwork: The Historic Palestinian Media Landscape

The media models installed by the Israeli state and the Israeli military government subsequent to the 1948 War inside Israel and the Six-Day War in the West Bank were to become formative frameworks for post-1994 Palestinian media. The distinct shift to a mobilized mode of expression for and on behalf of the Palestinians in the wake of the First Intifada and the Oslo Accords thus constituted an inversion of the hitherto Israeli-dictated repression of Palestinian media. The liberation of the Palestinian press “from the shackles of the [Israeli] establishment,”[15] came forth from vastly different media environments on both sides of the Green Line, reflecting the disparate political circumstances and the dynamics of the relationship between Israeli and the respective Palestinian communities. Indicative of the societal and political aftermath of the 1948 War, inside the 1948 borders an integrationist media model was developed by the Israeli victorious majority for the Palestinian vanquished minority of approximately 156,000, creating what Dan Caspi and Mustafa Kabaha succinctly term a ‘media-for’ model. The production of Arabic media by the Israeli establishment, which included the Israeli government, various Zionist political parties, and the Israeli communist party in its various reincarnations, was meant to serve as a medium through which the Jewish majority could communicate with the minority, while simultaneously reducing the objections of the minority to the national goals of the majority and diminishing the realization of Palestinian national ambitions.[16] In al-Yawm [Ar. the day] (1948-1966), a newspaper affiliated with the ruling party Mapai and its satellites in return for generous (financial) support, the Israeli state was therefore presented in a positive light resulting from “the benefits and the fruits of Israeli democracy,” as indicated in the writing of Wafi’a Iqdays who informed his readers in June 1950 that “anyone who claims that the situation has not taken a turn for the good since the end of the fighting probably suffers from the ‘malady of exaggeration’.”[17]

Although the termination of the military government in 1966 led to increased freedom of movement among Palestinian journalists and, consequently, access to their target population, the amalgamation of previously installed legalized modes of censorship and the incorporation of the newly occupied territories meant that a media for and by Palestinians remained elusive. Fueled by a heighted climate of suspicion resulting from exposure to East Jerusalem and West Bank newspapers, previous adoption of the British Ordinance of 1933 and the Defense (Emergency) Regulations of 1945 by the Ministry of Interior in 1948 enabled close surveillance of Arabic press produced by Palestinians.[18] Content related to the conflict, the coverage of settlements, land expropriation and discrimination towards the Palestinian population, both in the occupied territories and inside Israel, were particularly subject to scrutiny by censors, leading Palestinian journalists to engage in self-censorship to avoid attracting warnings or suspensions. Moreover, the continued dependence on political funding and the partisan nature of Arabic newspapers led to a dearth in Palestinian readership. As a result, between 1967 and 1983, circulation numbers remained largely similar to the first period, with the most popular daily newspaper, al-Ānbāʻ [Ar. the news], a mouthpiece for Israeli government policies, only reaching a circulation of approximately 4-6,000 in spite of distribution on both sides of the Green Line and a rising literacy rate.[19]

In contrast to the media landscape inside the 1948 borders, a popular Palestinian press did emerge in East Jerusalem and the West Bank in the wake of the 1967 War, albeit under heavy restrictions imposed by the Israeli state. In addition to the media-for model, namely a media wholly owned and managed by the Israeli military regime, a Palestinian press came forth out of the merger of West Bank newspapers and the forced move to Amman in March 1967 under King Hussein bin Talal. Al-Quds, representing the merging of al-Difāʻ [Ar. the defense] and al-Jihād [Ar. the (inner) struggle or holy war], became the first ‘independent’ daily to obtain publication rights from the Israeli military government and, despite its initial pro-Jordanian stance, became the most popular publication in the territories.[20] Yet, as was the case for Palestinian media in Israel, a fully independent press in the newly occupied territories remained absent. Similar to their predecessors—the Jordanians and the British—the Israelis applied legal means to subdue any mediated Palestinian (and Arab) nationalism in annexed East Jerusalem and the occupied West Bank, including by censoring any criticism of the Israeli occupation and thwarting usage of the media as a medium for political mobilization. The issuing of military orders together with the adoption of the above-mentioned British press regulations meant that Palestinian publications in the territories operated under more severe constraints than those published inside the 1948 borders.[21] As such, the system of external prior censorship consistent with the 1945 Emergency Regulations was bolstered by military orders issued from 1967 onwards which forbid the publication of anything that according to the military court was deemed of “political significance” and “prejudicial to the defense of [the state] or to the public safety or to public order.”[22]

News items of political significance were not limited to material that incited violence, hatred, or civil disorder, as claimed by the Israeli authorities. Instead, in his 1983 work, Meron Benvenisti, the former Deputy Mayor of Jerusalem, noted that censors’ primary concern was “to eradicate expression that could foster Palestinian nationalist feelings, or that suggest[ed] that Palestinians are a nation with a national heritage,” including by omitting text containing the word ‘Palestine’.[23] It was because of Israeli authorities’ tendency to view Palestinian publications as propaganda organs rather than vehicles of news that one Palestinian journalist concluded in 1986 that Israel’s censorship measures were designed to “censor our heritage, our history, and our culture, in order to deprive us of our Palestinian consciousness.”[24] Indeed, contemporary reports on censored content by human rights organizations indicate that, in addition to words such as suffering, colonialism, Jewish gangs, and Zionism, words that had taken on a symbolically-loaded meaning were targeted for censorship, including kifāḥ [Ar. struggle], ṣumūd [Ar. steadfastness] and ʻawdah [Ar. return].[25]

The Emergence of a Mobilized Palestinian Press

The existence of censorship practices in the post-1967 era in East Jerusalem and the West Bank proved formative for the conception of media as a potential mobilization medium on behalf of the Palestinians, which was to be practically realized following the Oslo Accords. Palestinian journalists living under previous Israeli censorship noted that, in theory, it was the task of journalists “to mobilize the masses against the occupation and the escalation of national activities in that struggle.”[26] However, it was not merely the systematic prevention of mediated resistance under Israel’s military government that informed the emergence of a mobilized media under the Palestinian Authority. With the 1980 amendment of the Tamir Law, any material deemed to support terrorist organizations was made punishable by a prison term of up to three years, a fine, or both; consequently, any mediated mention of the PLO, considered a terrorist organization under Israeli law until 1993, was curtailed.[27] For Al-Quds, a newspaper located in annexed East Jerusalem and therefore jurisdictionally part of the state of Israel, the Tamir Law meant that the publication’s pro-PLO stance following the cessation of talks between Arafat and King Hussein in February 1986 and Israeli officials’ accusation of Al-Quds accepting money from the PLO went hand in hand with a mass clampdown on the newspaper.[28] Publication restrictions were further intensified with the outbreak of the First Intifada in 1987, when any material that could be interpreted as implicitly supporting the PLO became subject to censorship. As such, the newspaper’s explicit support of the PA following the Oslo Accords,[29] part and parcel of Nakba media output, formed the realization of a mediated collective political engagement and consciousness which had previously been thwarted.

Research conducted on the emergence of an independent Palestinian press inside the 1948 borders in the mid-80s suggests that financial motivations proved decisive in the development of a media for and by the Palestinian minority. Hanna Adoni, Dan Caspi, and Akiva Cohen argue that the rise of privately-owned newspapers resulted from the uncovering of substantial advertising potential among Palestinians, thereby immunizing newspapers from the effects of political subsidies and pressure.[30] Yet, while the discovery of new economic opportunities might have enabled the establishment of Palestinian commercial newspapers, their resonance among readers should be considered in the contemporary political climate and in the context of what Margaret Gibson and John Ogbu term “an involuntary minority.”[31] Thus, the Palestinian public’s withdrawal from the Israeli public sphere in the late 1980s, resulting from the experienced marginalization of Palestinian affairs, bolstered cultural autonomy, because as the poet Samih al-Qasim and editor of Kul al-Arab stated in 1993: “We don't want a Berlin wall between Arabs and Jews. But it is natural that we would want to feel more comfortable with our language, with our culture, with our spiritual needs. We want our own theater, which doesn't exist now. We need to rebuild ourselves. We have been in a siege since 1948. We are unknown. For decades, nobody has heard about us.”[32] The need for a creation of what Amal Jamal describes as “a counterhegemonic public space” was reinforced in the wake of the outbreak of the First Intifada which brought about a surge in Palestinian identity at the expense of a hybrid identity, in part, Jamal claims, as a result of new Arabic publications demonstrating unsurprising empathy with the Palestinian side.[33] Despite a continued dependence on (Israeli-Jewish) advertising firms, for the first time, Palestinian media, located in the eye of the storm of the Arab-Israeli conflict, could express the unique circumstances of the Palestinian population in Israel and respond to cultural and political events in relation to their past, including, as will become evident below, by portraying the Nakba as an ongoing event, contextualizing relations with the dominant majority.[34]

Exposing the Nakba as a Historical Event: A Land with a People

Five years after the 1993 Declaration of Principles and two years prior to the outbreak of the Al-Aqsa Intifada, Palestinians in the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Israel commemorated the 50th anniversary of the Nakba. Mirroring the collective preoccupation with the past, Palestinian media partook in what can be identified as the first mediated Nakba ‘anniversarial event’, with Nakba output surfacing in the weeks and months preceding what was to become Nakba Day.[35] In an interview, Wadiah Awadah, a former journalist at Kul al-Arab responsible for the consistent publication of refugees’ narratives in the lead-up to the 50th anniversary, maintained that the increased media output prior to the anniversary was indicative of the heightened preoccupation with the Nakba on its upcoming 50th anniversary and, at the same time, reflected readers’ interest in writings on the Nakba that challenged the official Israeli narrative.[36]

The novelty of Nakba media output on the occasion of the 50th anniversary is evidenced by both the placement of Nakba media output and the sheer amount of articles dedicated to the topic. In contrast to previous years, the examined newspapers’ front pages on Nakba Day reminded readers of the momentous commemorative events taking place, creating, in the words of Daniel Dayan and Elihu Katz, a ‘suspended mediation’.[37] Moreover, in the weeks prior to the 1998 anniversary and on the anniversary itself, Palestinian media on both sides of the Green Line provided readers with an historical overview of the displacement that took place in 1948 with the aim of revealing Israel’s “complete web of lies and rumors and historical falsities of a land without a people for a people without a land”[38] and, perhaps most importantly, exposing “the forgery of the Zionist claim that the Palestinian refugees left willingly following calls by their own leaders.”[39] Individual refugee stories deemed representative of the expulsion of the “more than 750,000”[40] Palestinians and of the 40,000 internally-displaced “present absentees” at the hands of the “Zionist gangs” not only laid claim to the pre-1948 cultural and physical landscape, but also attested to the ongoing ramifications of a forced displacement in line with the political landscape created in the aftermath of the 1948 War.[41] Demonstrative of the readership’s cadres sociaux,[42] Kul al-Arab disclosed internal refugees’ stories while Al-Quds concentrated on the plight of those living in refugee camps in the West Bank.[43]

The 50th anniversary of the Nakba in 1998, as the first mass mediated anniversarial event, also constituted a formative framework for Nakba Day mediation in subsequent years, during which newspapers have simultaneously acted as active participants in Nakba mnemonics and as ‘commemorative mobilization agents’.[44] In addition to giving prominence to the anniversary of the Nakba on their front pages, since 1998, the newspapers under review have offered what can be termed ‘commemorative prompts’, reminding their readers in content and in graphics of the year of the anniversary and calling upon them to participate in commemorative marches and festivals or, as Kul al-Arab put it in 1998, to “answer the call of the national and humanistic obligation to commemorate the Nakba memory and to revive the national memory and to assure the continuation of the struggle in a popular rally.”[45]

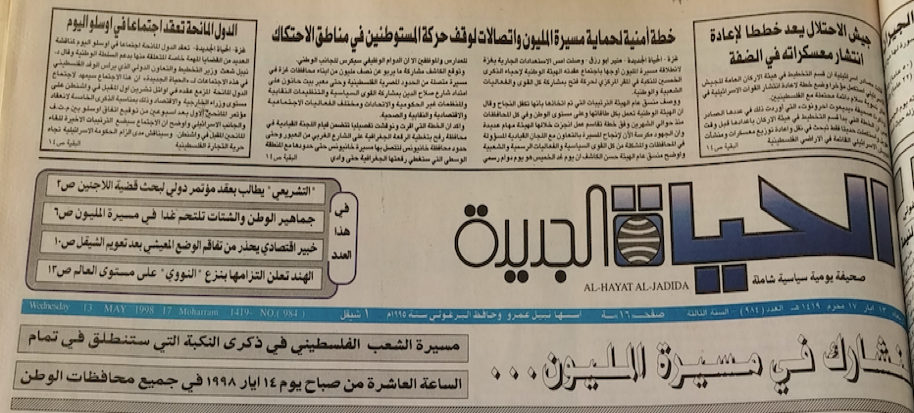

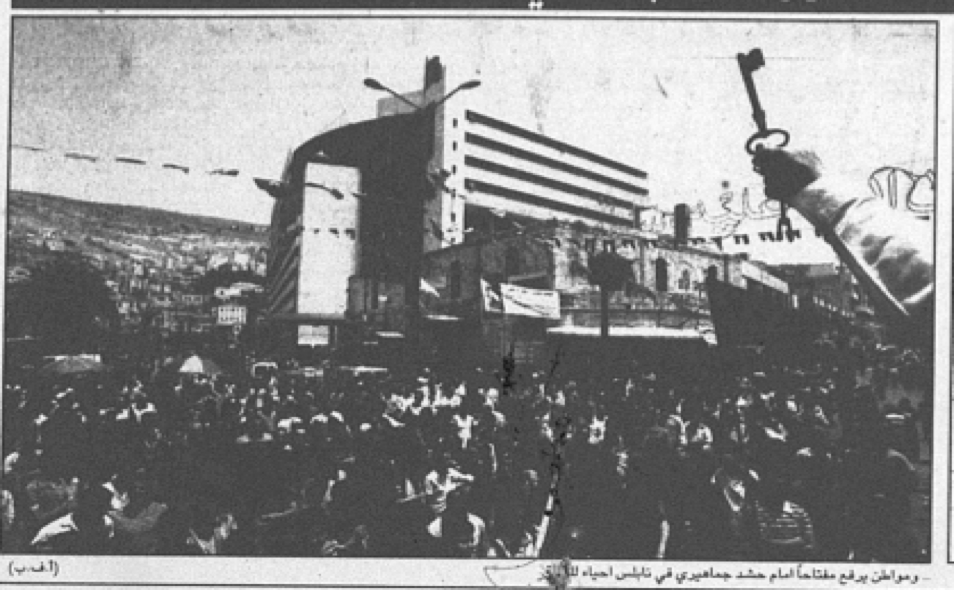

Figure 1.1. The Nakba as a mediated commemoration

“50 years of the Palestinian Nakba,” Kul al-Arab, May 15, 1998

Al-Quds, May 15, 1998

“Let’s participate in the March of the Millions,” Al-Hayat al-Jadida, May 13, 1998

On the 60th anniversary of the Nakba. General strikes among Arab student groups create high tensions in the country’s universities. Kul al-Arab, May 16, 2008

“68 years of the Nakba,” Al-Quds Online, May 15, 2016

“Citizens gather around the ‘64 years’ candles in Ramallah in preparation for the commemoration of the Nakba.” al-Hayat al-Jadida, May 15, 2012

A further textual commemorative reminder from 1998 is the placement of official political statements in Nakba anniversary issues, which in that year not only set out the legislative council’s roadmap for the reversal of the Nakba “in spite of entering the peace process,” but also called on the “masses to commemorate the anniversary of the Nakba extensively and […] to participate in the Palestinian March of the Millions.”[46] Consistent with the political landscape in the West Bank (and indeed Gaza), these official statements, typically only published in Al-Quds and al-Hayat al-Jadida,[47] have moved from representing the legislative council, virtually defunct since 2006, to incorporating the announcements of various political parties and semi-political commemorative agencies.[48] Following the split between Hamas and Fatah, official announcements by the Fatah-backed PLO, the Higher Committee for Nakba Commemoration and the PLO’s Refugee Department, calling upon “you in the homeland to take part as participants with us in a central rally and return festival today,” were firmly situated within the political framework approved by the Fatah-led Palestinian Authority (PA) in the West Bank.[49] Juxtaposing Hamas’ “prolonging of division and preservation of partisan interests [at] the expense of the supreme interests of our people and their national cause” with the PLO’s commitment to “national unity,” the anniversary of the Nakba thus became a political opportunity to garner support among those who believed in “the rights of our Palestinian people.”[50]

Preserving the Past for Future Generations: The Media as a Prospective Memory Realm

Although the above-mentioned commemorative prompts might point to a contemporary mnemonic preoccupation, media exposure to the anniversarial events of the Nakba is also considered a means of conveying the past to present and future generations in order to ensure knowledge of the past. Calls to transmit the Nakba to future generations have been identified from 1995 onwards, which emphasize external familial transmission alongside the media as a ‘prospective’ memory realm. The earliest materialization of the first can be found in Al-Quds’ issue of 10 April 1995. Here, readers are not only exposed to a reportage of the commemorative festival conducted on the 48th anniversary of the Deir Yassin massacre (9 April), but also to an explicit call by the contemporary governor of Ramallah and al-Bireh, Mustafa Aysha Abu Firaz, addressed to a “group of Deir Yassin scouts,” the “grandchildren of the strugglers” to become “the soldiers of the homeland [and] to remember with utmost emotion several of the homeland’s martyrs who with their blood gave water to the soil.”[51] Two years later, in 1997, al-Hayat al-Jadida dedicated two editorials to the media’s role as a formative realm of transmission. Criticizing the media’s own previous neglect of the Nakba and its anniversary, editorials by Hassan al-Kashif and Hafez al-Barghouti maintained the media’s responsibility to address the Nakba in the public sphere to “commemorate it and educate the youth on what happened and its significance,”[52] even if “the burden of memories abolishes the pleasures of life.”[53] When questioned about the timing of these editorials in the PA’s mouthpiece, Omar Hilmi al-Ghoul, a columnist for al-Hayat al-Jadida and former chief political advisor to the Prime Minister of Palestine, Salam Fayyad (2007-2013), emphasized the political transition in the wake of the Oslo Accords. Al-Ghoul contended that following the establishment of an independent Palestinian media, the duty to transmit the Nakba was amplified, because, as Al-Ghoul stated, “I, like other officials, am responsible for expressing the interests of my people […] our heritage, culture and national identity cannot be forgotten.”[54]

Beyond the effects of the Oslo Accords on media’s role as a ‘prospective memory agent’, the lingering mortality of first-generation Nakba eyewitnesses, inferred in al-Kashif’s article, should not to be neglected.[55] Indeed, for Awadah, the increased attention given to the Nakba from the mid-90s onwards also spurred from the realization that transferring stories of the Nakba to future generations was pertinent, as “eyewitnesses of the Nakba might die without sharing their stories.”[56] In order to “forge a Palestinian identity and record history,” Awadah “started collecting stories about the Nakba and the time before the Nakba so that our narrative will remain alive [and] so that the new generation would know what happened in Nakba.”[57] Yet, while the media’s self-proclaimed role as an agent of Nakba transmission can be found explicitly in editorials in the lead-up to the 50th anniversary and implicitly in reportages on the 50th anniversary itself, calls for Nakba generational transmission have most consistently appeared from the mid-2000s onwards, in editorials calling for extra-media educational and commemorative initiatives and through the collection and transmission of refugees’ testimonies.[58] Reflective of the decreased life expectancy of the remaining first-generation Nakba eyewitnesses,[59] refugees representing the jīl al-Nakbah [Ar. the Nakba generation][60] have therefore been commanded to pass on the stories to “the grandchildren,” the jīl al-Awslū [Ar. the Oslo generation], “[to] refute the statement made by the founders of the Jewish state that the adults will die and the children will forget.”[61]

The Nakba as a Present Continuous: Nakba Mediation Inside the 1948 Borders

Mediated calls for engagement with Nakba mnemonics reflect the Palestinian communities’ particularistic relation with the Israeli state, thereby testifying to the notion that mass media do not act in a vacuum, but rather interact within the historical, cultural and political circumstances of each society, as well as its contemporary interactions with other (dominant) groups.[62] Inside the 1948 borders, Nakba mediated output has consequently simultaneously constituted an interpretative framework, reflecting the Palestinians’ minority status, and an analogical tool, exposing the ongoing manifestations of the Nakba resulting from their minority status. Israel’s marginalization of the Palestinian narrative in the educational system and attempts to prevent Palestinian commemoration of the Nakba are clear examples of the former, albeit with different temporal manifestations. Whereas the failure to convey the Palestinian conception of the 1948 War to Israeli and Palestinian students can first be identified in 1998, implicitly inferring the contemporary content of textbooks which largely failed to convey the Palestinian conception of the 1948 War,[63] right-wing organizational thwarting of Nakba commemoration on Israel’s Independence Day surfaced ten years later, in 2008.[64] Following the 60th anniversary of the Nakba, Kul al-Arab’s front page informed its readers of the clashes that had taken place the previous day at Haifa University when Palestinian students sought to commemorate the Nakba and were confronted by members of Hatikvah [Heb. the hope], a far-right political party established the previous year under the leadership of Ayre Eldad in order to counter Likud’s implementation of “the policies of Peace Now” and to expose the Palestinian narrative as “a lie.”[65] In addition to exposing attempts by recently-established far-right groups such as Hatikvah and Im Tirtzu[66] to prevent commemoration, in the wake of the Knesset’s 2009 approval of a preliminary Nakba Bill and the subsequent ratification of its amendment in 2011,[67] Nakba mediated output has emphasized collective mnemonics in spite of the “racist and dangerous law”[68] which seeks to “ban the commemoration of the Nakba”[69] and leads to “a worsening of [Israeli] denial of the Palestinian Nakba.”[70]

Contemporary marginalization is not solely deemed emblematic of Palestinians’ present-day status in Israel; rather, it is the foundational event creating this involuntary minority that spawns the conception of the Nakba as an analogy for subsequent marginalization, or a present continuous Nakba. Indeed, anniversarial Nakba mediation in Kul al-Arab does not conceive of the Nakba as a past event, but rather as “an ongoing Nakba,” since, as one article put it in 2010, al-Nakbah mā zālāt mustamirah [Ar. the Nakba does not stop continuing].[71] Apart from emphasizing “racist discrimination and apartheid,”[72] and “the [geopolitical] division of the Palestinian people into five groups,”[73] materialization of the continuous Nakba is principally found in Israeli land confiscation policies and contemporary Palestinian displacement inside the 1948 borders. Although media dedicated to present-day Palestinian displacement at the hands of the Israelis can be identified from the late 1990s onwards,[74] it is only a decade later that it is explicitly placed in the context of an ongoing Nakba, itself an outcome of what is termed the “ongoing Zionist project.”[75] Following the concept of a Zionist transfer policy,[76] this project, which is equated with the “Judaization of the land” and “the ethnic cleansing [of Palestinians],” is deemed perceivable in contemporaneous house demolitions “under the pretext of illegal construction,” the Judaization of East Jerusalem and the failure to implement UN resolution 194.[77] Indicative of the historical implementation of policies which enable these practices, including the designation of “open landscape areas”[78] in East Jerusalem following the adoption of the 1980 Basic Law,[79] materializations of the ongoing Nakba are identified year-on-year, albeit in a contemporary context.[80] In 2012, a Kul al-Arab article invoking a speech by the party leader of Balad [Ar. country or land], MK Jamal Zahalka, noted that “Israel continues the war it began in 1948 [which sought] to plunder the land of the homeland” with reference to a “series of racist confiscation laws [recently] passed by the Knesset under the Netanyahu government.”[81] A year later, a report on the displacement of 14,000 (Bedouin) Palestinians and the destruction of 2,000 homes in the Negev was considered an indication of “ongoing Israeli policies [aimed] at uprooting Palestinians from their land to this day.”[82]

Mobilizing the Past: Nakba Mediation in East Jerusalem and the West Bank

Beyond conceiving of the Nakba as an interpretative framework, emblematic of today’s occupied and annexed state, Nakba anniversarial mediation in the West Bank and East Jerusalem has taken on a retrospective analogical role to illustrate the occupied/annexed fate of the Palestinian majority in the West Bank and East Jerusalem.[83] Symbolizing both the emergence of nationalist goals and, through the Nakba’s continued presence, a necessary adherence to their objectives in mnemonic activities, Nakba mediation has become a primary means of expressing Palestinian national concerns and goals. Chief among these nationalist aims are implementing the right of return, challenging the ongoing Israeli occupation and the illegal dispossession of land earmarked for the Palestinian state in the Oslo Accords and, in addition to this, advancing the establishment of a Palestinian state with East Jerusalem as its capital.[84] Contemporary politics seek to contextualize the need for these nationalist objectives—a necessity which is further exemplified by recurrent employment of the symbolically-charged terminology of tamasuk [Ar. holding on] and ṣumūd [Ar. steadfastness]. As such, amid the Oslo Accords, adherence to the right of return is stressed by opposition parties, as seen in an April 1994 Al-Quds interview with the general director of the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP), Nayef Hawatmeh. In line with the party’s perception of the Oslo Accords as a surrendering of Palestinian rights, the article criticizes the absence of any meaningful discussion concerning the “sacred right of return [which] is fixed according to UN Resolution 194 [1948] and in Resolution 237 [1967].” In order to “restart negotiations and rebuild the [peace] process,” Hawatmeh therefore calls for a safeguarding of “the return of the displaced without pre-conditions.”[85]

While what the Palestinian historian Abdul Latif Tibawi termed an “Arab Zionism”,[86] can be identified in subsequent years, including in pictures of keys as an ever-present reminder of sanaʻūd [Ar. we will return],[87] explicit criticism of the PLO and, subsequently, the PA’s handling of the refugee problem is practically non-existent.[88] Studies conducted on freedom of expression in Palestinian press, including (semi-)independent and wholly-owned outlets by the PA, demonstrate that despite the absence of censorship regulations as they existed until 1994,[89] the PA has exercised its own form of control over media institutions.[90] The encouragement of self-censorship through a carrot and stick policy and the existence of overt, external censorship through detaining journalists and withdrawing publication licenses even led a 2000 Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) report to claim that the “censorship, intimidation, and arbitrary arrests of Palestinian journalists that marked full-fledged Israeli occupation are now practiced by Palestinian president Yasser Arafat and his coterie.”[91] The existence of censorship practices is evident in Nakba meditation on the right of return. Although articles published in the aftermath of the Oslo Accords firmly reject “all solutions that do not provide the right of return to four million refugees”[92] and any negotiations and wavering of this “sacred right”[93] based on any “statute of limitations,”[94] the PA’s own negotiations on this right are not mentioned. Even in the wake of Al Jazeera’s publication of the Palestine Papers,[95] responsibility for “the perpetuating of the Nakba”[96] through the existence of the refugee problem, according to the PA’s chief negotiator Saeb Erekat, needs to be firmly placed with Israel and the international community, and his claim of a sole “solution to the refugee issue based on UN resolution 194”[97] goes wholly unchallenged.

The allusion to the international community alongside Israel, as seen above, should not infer that the international community is deemed equally accountable for the existence and perpetuation of Palestinians’ national problems. Indeed, while articles published on Nakba Day note that the anniversary is welcomed as a means of reminding the world “of the historical injustice inflicted upon our people”[98] and to demand “the world’s commitment to international law,”[99] it is Israel that is chiefly held responsible for “challenging international laws, regulations, treaties and the will of the international community.”[100] Beyond

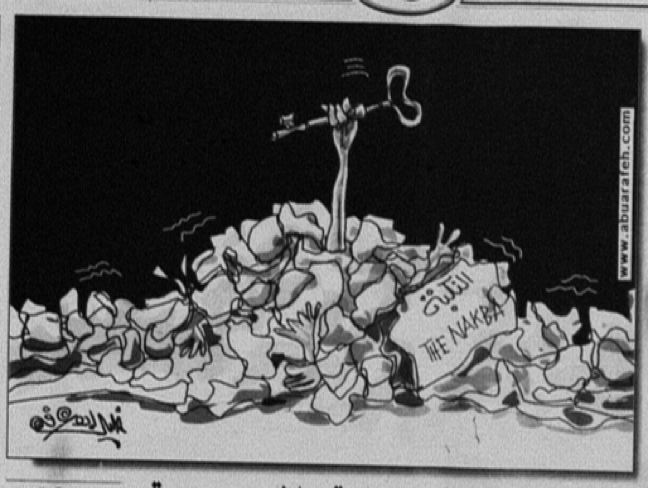

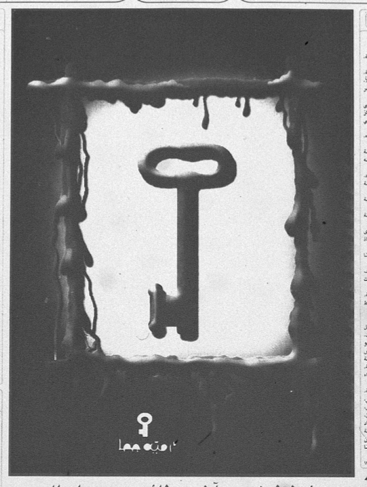

Figure 1.2. The key and the dream of a return

Al-Quds, May 14, 2001

al-Hayat al-Jadida, May 14, 2005

al-Hayat al-Jadida, May 16, 2008

al-Hayat al-Jadida, May 15, 2012

“Returning to Haifa.” Al-Quds Online, May 15, 2016

“We will return.” Al-Quds Online, May 14, 2016

the “continuous occupation” which, according to President Mahmoud Abbas in 2008, characterized as the “the permanent Nakba,”[101] land confiscation is deemed the principal defiance of international law and of “individual and collective [Palestinian] rights.”[102] In response to the maintenance of settlement activity in the West Bank and East Jerusalem in line with Netanyahu’s 1997 ‘Allon Plus Plan’[103] and the concurrent implementation of a secret plan by the Israeli Civil Administration to dedicate ten percent of the West Bank to further settlements,[104] annual Nakba mediation since the mid-90s has consistently proclaimed “the destruction of the two-state solution.”[105] Deriving from “Zionist colonial aggression,”[106] the destruction of the peace process is principally characterized by the “continuation of the settlement policy,”[107] “the Judaization of East Jerusalem,”[108] and, since 2003, “the racist separation wall.”[109]

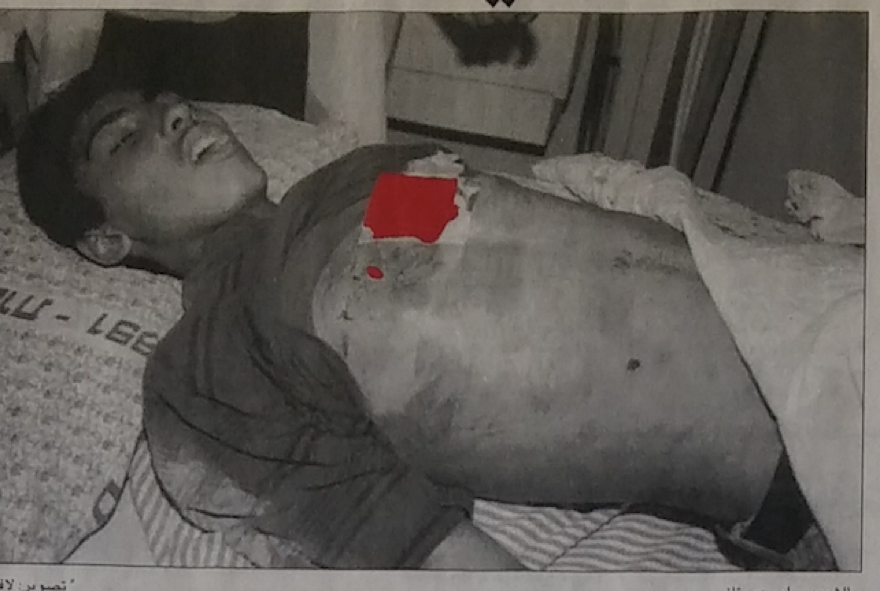

In order to confront “these serious challenges [to] our national project and the goals of people [to live] in freedom and independence,”[110] Nakba mediated output has sought reinforcement of, and adherence to, the so-called “fixed national principles,”[111] which dictate “no peace or security or stability unless the Palestinian refugee issue is resolved based on resolution 194; return, self-determination and establishment of the [Palestinian] state.”[112] In addition to participation in mnemonic activities to “show national anger,”[113] loyalty to these principles is advocated through holding on [Ar. tamasuk ] to the land in spite of “incursions into Palestinian territories”[114] and, at times, hailing violent confrontations with “occupation forces.”[115] In the latter context, it is worth noting that in al-Hayat al-Jadida’s 2000 Nakba Day black and white edition, the blood of a “martyr who died in [Nakba Day] clashes at Qalqilya” did appear in color on the front page; thereby suggesting that the “confrontation with occupation soldiers to stress their commitment to the right of return and refuse nationalization projects” validates an interruption in the commemorative mediation.[116] Importantly, glorification of violent confrontations prior and subsequent to the Al-Aqsa Intifada—deemed a renewal of the “people’s allegiance [to the land] with blood”[117]—also indicates that existent mobilization efforts in Nakba meditation do not necessarily only coincide with times of increased violence or heightened political strife.[118]

Figure 1.3. Holding on to the ‘national goals

“The remaining Palestinian people [held captive by] settlements.” al-Hayat al-Jadida, May 14, 1998

al-Hayat al-Jadida, May 15, 2000

Crucially, the achievement of the “fixed national interests” is not solely dependent on a demonstrative social mobilization on Nakba Day, but also on the existence of national political unity.[119] Repeated calls in Nakba media output seeking “unity among all political factions” can be traced to two distinct periods: In the wake of the 1993 Oslo I Accord and, more consistently, following the outbreak of what Joel S. Migdal termed “a Palestinian civil war” between Hamas and Fatah in 2006/7.[120] In the period under examination, the advancement of a “national unity” and “true solidarity” in Nakba mediation forms a mirror into the domestic Palestinian political landscape.[121] As such, while in the period following the 1993 Oslo Accords, editorials and news articles stress the creation of “unity among all Palestinian factions [in] the ongoing negotiations”[122] and the “solidification of the work of the PLO to strengthen the unity of our people,”[123] the rift between Fatah and Hamas prompted calls for “national unity [through] political reconciliation.”[124] Yet, despite the difference in timing and in political objectives, both in the aftermath of Oslo and subsequent to the various reconciliatory attempts between Hamas and Fatah,[125] advancement of domestic political unity within Nakba mediation must be understood as a clear engagement with its neighbors. Moving from the political consolidation of the PLO in the 1990s to the pursuit of a new Palestinian unity government from the late 2000s onwards, Nakba mediation in East Jerusalem and the West Bank thus forms a continual explicit negation of Israel’s “no partner for peace narrative,”[126] all the while holding on to “the supreme interest of our people and their national cause.”[127]

Concluding Remarks

In the build-up to the 50th anniversary to the Nakba, Palestinian media on both sides of the Green Line collectively turned their attention to the past. Bolstered by the post-Oslo media landscape in the West Bank and East Jerusalem and, inside the 1948 borders, the perceived capitulation of Oslo, Nakba anniversarial mediation became a means of expressing the communities’ concerns in coherence with the readerships’ cadres sociaux. The commemorative prompts identified within Palestinian media, which originated during the 1998 anniversary, moreover, both testify to the media’s heightened role as an agent of transgenerational transmission and equally reveal usage of Nakba mediation as a form of ‘commemorative mobilization’.

Forming the inverse of Israeli-dictated mediation in the wake of the 1948 and 1967 War, post-Oslo media for and by Palestinians reflects the communities’ relations with Israeli hegemony. Demonstrative of its readership’s principal concerns, Kul al-Arab has presented the Nakba as an interpretative framework for contemporary grievances resulting from Palestinians’ status as an involuntary minority in Israel. As such, within anniversarial mediation, the Nakba as a continuous present does not simply signify the historical fate of internal refugees, but furthermore is considered the foundational event which generated the marginalization experienced at the hands of the majority. In addition to legislative attempts by far-right Israeli groups to thwart Nakba commemoration, which culminated in the 2009 Nakba Bill, the ongoing Nakba is presented in the framework of a continuous Judaization of Palestinian land. Considered symptomatic of the Zionist transfer policy, Nakba media output thus presents “the ethnic cleansing” [128] of Palestine both as an outcome of the continued implementation of pre-Oslo legislation and the introduction of new laws, including the 2009 Land Administration Law which allows refugees’ land to be sold off to private investors and placed beyond future restitution claims.

Nakba anniversarial mediation in the West Bank and East Jerusalem, similarly to inside the 1948 borders, illustrates the Palestinians’ particularistic relations with Israeli hegemony, shedding light on the majority’s occupied/annexed fate. Application of the Nakba as an interpretative framework and, simultaneously, an analogical tool testifies to the mediated expression of what McQuail defined as national goals. Through repeated usage of previously censored symbolic terminology, the readership of the semi-independent Al-Quds and the PA’s mouthpiece, Al-Hayat al-Jadida, is admonished to adhere to these national objectives, which call for an end to “the permanent Nakba”[129] through a resolution to the refugee problem, the right of self-determination and the establishment of a Palestinian state.

Yet, invocation of the so-called fixed national principles, as expressed in the publication of (semi)political mnemonic reminders, is not only meant to advance collective adherence to national objectives but, importantly, seeks to challenge the main actor deemed responsible for their suspension: Israel. Charged with the destruction of the two-state solution through repeated and, as revealed in 2012, clandestine settlement incursion into the Palestinian state to-be, Nakba mediated output has consequently become a realm of collective social mobilization against ‘the Zionist entity’, albeit one that does not deviate from the politically-accepted discourse of the PA. A comprehensive metaphor for the effects of ‘Zionist colonial aggression’ and its ongoing implications for daily Palestinian life, Nakba media output has therefore come to embody all Palestinian suffering—by refugees and non-refugees alike—at the hands of the Israelis.

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub