Issue 37, Winter/Spring 2024

https://doi.org/10.70090/CN24EMND

Abstract

Tunisia’s Jasmine Revolution facilitated the development of the nation’s first press freedoms. The success of the 2011 revolution is often attributed to social media, which played an influential role as a means of catalyzing resistance and communicating atrocities. However, social media was also used as a tool of disinformation. This study assessed how future journalists who had not worked in the field prior to the establishment of tentative press freedoms used social media in their reporting. This examination of Tunisian journalism students’ uses, values, and role perceptions regarding social media during a key period of post-revolution democracy building may serve as a barometer for the future of the field. Results demonstrate respondents primarily use social media to track breaking news, keep in touch with audiences, and find information. These uses most strongly correlate with the monitorial role, which is most closely associated with established democracies. Overall, respondents indicated the impacts of social media on their individual work were favorable.

Introduction

The Jasmine Revolution in Tunisia ousted dictator Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in 2011, which resulted in the state-run news media being replaced. Subsequently, the nation’s first democratically elected president and parliament rose to power and enacted temporary policies that protected news media independence. During the Arab Spring, social media served as a key platform for both catalyzing and documenting resistance in the streets and organizing movements (Howard et al. 2011; Karolak 2017). Prior to the revolution, Tunisian activists believed that “social media was the only credible source of news” (Karolak 2017, 206). Social media enabled users to amplify their voices beyond the reach of state-controlled news media in ways that were instant, global, and could remain anonymous. The nation of Tunisia boasts a large youth population as the median age is 32.7 years old (CIA 2021) and one of the highest mobile phone user rates in Africa (International Trade Administration 2020). As such, many users foregrounded their values onto social media as a democratizing tool (Karolak 2017). In 2019, 75 percent of surveyed Tunisians indicated that social media impacted their access to information (CIGI-IPSOS 2019). How aspiring journalists perceive and use social media in their pre-professional work may provide a barometer for how they will engage with social media when they enter the field. This is particularly pertinent for those students who decided to major in journalism after the revolution.

For Tunisian students studying to be journalists, the revolution occurred during a formative time that shaped their understanding of democracy and use of social media. Unlike journalists who previously labored under state censorship, student journalists are learning the craft during a new—albeit tentative—era of press freedom that is inextricably linked to social media. Using survey data, this study explored how future journalists in an emerging democracy use social media in their work, understand its impacts on their work and the field, and conceptualize social media in terms of their future professional roles. This work adds to the body of scholarship covering the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region that examines how journalists interact with social media. Thus far, this body of research primarily focused on established democracies with long-standing journalistic freedoms in which social media has been introduced into traditional systems (Hanitzsch et al. 2019; Mellado et al. 2013). This research examines the attitudes and habits of future journalists as it pertains to social media and journalism in an emerging democracy. As such, this examination has unique potential to illuminate a news media ecology that was never subjected to the decades-old field norms that predate mobile technology.

Literature Review

Over the past fifteen years, the development of digital technologies has created unprecedented opportunities for journalists to publish news instantly and globally, quickly find sources and information, monitor the work of other journalists, as well as interact with audiences via social media (Nielsen 2013). In the context of Tunisian journalism, these digital affordances precede the establishment of a free and independent press. These technologies also played a role in the revolution, which correspondingly facilitated press reforms. Throughout the Jasmine Revolution in Tunisia, websites and social-media platforms helped independent bloggers, citizen journalists, and organizers reach their audiences during an era of state-controlled news media (Giglio 2011; Lim 2013; Maurushat et al. 2014). Students pursuing journalism degrees in Tunisia will enter a field where online journalism predates press freedom. Simultaneously, most news media outlets are privately held (BBC 2023) and legitimate concerns regarding press freedoms remain.

Although current Tunisian President Kais Saied pledged support for press freedoms, which was supported by the fact the state-run wire service actively covered public protests against the president. However, Saied also passed a law sentencing anyone who reports ‘false information’ to jail time (Amara 2022). Further, bloggers have been arrested for criticizing elected officials (Human Rights Watch 2019). Moreover, media ownership concentration continues to pose a threat to the free flow of information, which includes some outlets owned by relatives of former dictator Ben Ali (Reporters Without Borders n.d.). Although Tunisia rose 25 spots in the 2019 Press Freedom Index published by Reporters Without Borders—moving from 97th to 72nd place—it dropped to 73rd in 2020 due to violence against journalists (Reporters Without Borders 2021). While codified through the legal system in Tunisia, most of the press freedom laws are temporary and not reliably enforced. The situation shifted when President Saied froze parliament on July 25, 2021. Two months later Saied announced he would rule the country via presidential decree, which correspondingly suspended a large section of the Constitution (Yee 2021). Within days, Reporters Without Borders called upon newly appointed Prime Minister Najla Bouden to uphold the country’s press freedoms (RSF 2021). In February 2022, the Tunisian president dissolved the Supreme Judicial Council and issued a short-lived decree that allowed him to dismiss judges. During this time the president has only granted a single interview to Tunisian media and instead relies upon the official presidential Facebook account to serve as a communication channel. Further, the president currently has no spokesperson. Meanwhile, the Tunisian journalist’s union (Syndicat National des Journalistes Tunisiens) released several statements that condemned assaults against journalists, continued threats against freedom of expression, and called on the government to respect the right to access information (SNJTa 2021; SNJTb 2021). The Tunisian transition to democracy is now at stake because of these turbulent events.

Journalists and Social Construction of Technology

The same digital tools that informed citizens during the revolution are exploited by those who wish to control the press. For example, in the early post-revolution years the powerful political party Ennahdha used Facebook to attack and discredit journalists (Yacoub 2017). Social Construction of Technology theories reveal how users foreground their values onto the technologies they use—if they choose to use them. New technologies are born with different affordances, which embodies new ways of doing things that were not previously possible via older technologies (Gane and Beer 2008). However, users do not always use those technologies in the way they were intended. Rather, users socially shape technologies based on the ways they use them (Kline and Pinch 1996). Thus, how pre-professional Tunisian journalists use social media may reveal what they value. Rather than taking a technologically deterministic approach by assuming future journalists in an emerging democracy would use and value social media in the same manner that journalists in long-established democracies do, this study explored the context of Tunisia as a nascent democracy. Studies that examine how journalists in long-established democracies with strong press freedoms—such as the United States and England—have largely revealed that journalists perceive social media as a threat to their journalistic authority and primarily conceptualize it as another publishing platform, rather than a means of interacting with the audience for sourcing or feedback (Carlson and Lewis 2015; Singer 2006; Singer 2014; Powers 2012). This resistance to social media has mostly been attributed to traditional field norms rooted in new institutionalism or retrenching traditional journalistic norms to preserve its identity (Cook 2006; Sparrow 2006; Vos 2019). As a result, it is important to investigate how journalists experiencing the first taste of press freedom might interface with digital technologies, particularly as it relates to newsrooms that haven’t yet developed institutional norms.

New Institutionalism vs. New Democracy

New institutionalism and professional roles are inextricably linked. Yet studies examining how journalists conceptualize their professional roles have primarily focused on the West and positioned democracy as a necessary precursor for journalism (Hanitzsch and Vos 2018). In the digital era, scant attention has been paid to the work of journalists in emerging democracies. As such, this research seeks to provide insight into that context with a case in North Africa. Tunisia provides the opportunity to examine a field establishing its first wave of independence in a digital era. In her interviews with Egyptian and Tunisian journalists working after the Arab Spring, Allam (2019) found them to be generally open to the opportunities and possibilities enabled by interacting with social media, particularly in terms of increasing their audiences and receiving viewer feedback. Increasing audience size is a primary goal in journalism but receiving audience feedback has not been a traditional value of journalists in established democracies (Singer 2006; Singer 2009; Singer 2014). This is particularly true as it pertains to feedback via social media that may be public. Allam concluded that Egyptian and Tunisian journalists could best use social media to engage with the audience, listen to their concerns, and learn about their ideas for solutions to further democratic gains in a “constructive-interactive” model of journalism (Allam 2019, 1290). Allam’s findings present a sharp contrast to studies conducted in established democracies, which found that journalists largely don’t care about audience feedback and instead perceive it as a threat to their own expertise and sense of professional identity (Carlson and Lewis 2015; Deuze 2005; Grubenmann and Meckel 2017; Nielsen 2013; Singer 2006; Wahl-Jorgensen 2015). Most of this work focused on the tensions between journalists and audiences versus the different values of journalists within the newsroom. (Bossio 2017). This research examines Tunisia at a key time in the development of journalism, which is an understudied location. The literature review provides context from previous studies of journalists in established democracies interacting with social media. However, the researchers do not presume that Tunisia—or any emerging democracy—should strive to emulate the U.S. or Western Europe. The case of Tunisia, where digital technologies predate the free press, may illuminate how future members of the field value and socially shape digital technologies. This is especially pertinent as it relates to journalism students who are digital natives.

Role of Social Media in the Tunisian Revolution

Social media played a central role in the revolution by providing a platform for conversations and serving as a vector for democratic ideas (Howard et al. 2011). In the early 2010s, Facebook was—and still is—Tunisia’s dominant social-media platform. Tunisia had 2.3 million Facebook users in early 2011, which vastly eclipsed Twitter’s 35,746 users during the same time (Salem and Mourtada 2011). During the uprising, the number of Facebook users grew by seventeen percent as compared to ten percent in the same period the prior year (Salem and Mourtada 2011). A survey determined that a third of Tunisian Facebook users reported using the platform during the civil movement to spread information. Another third used it to raise awareness inside the country regarding the causes of the uprising and nearly a quarter used it to organize actions and manage activists (Salem and Mourtada 2011). Almost ninety percent of Tunisians used social media to find news and information about the uprising, which far outstripped the 35.71 percent who relied on state-sponsored media (Salem and Mourtada 2011).

Although Western news media accounts regularly described the Tunisian Revolution as a Twitter revolution (Kahlaoui 2013), Twitter was primarily used to disseminate news outside of Tunisia. Within the country, Twitter did play a role in coordinating demonstrations and exchanging information while emerging “as a key source for real-time logistical coordination, information and discussion” (Lotan et al. 2011, 1377). Twitter users helped construct the narrative of the revolution through their use of hashtags, such as #sidibouzid, which was the hometown of Mohamed Bouazizi (Lotan et al. 2011). On December 17, 2010, Tunisian street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi self-immolated to protest the government’s confiscation of his produce cart scales. The event, which has been portrayed as the spark that ignited the Jasmine Revolution, was seized upon by Tunisian online activists to highlight the regime’s abuse and demand human rights (Kahlaoui 2013; Lim 2013). Soon after, online groups formed, and protest videos were shared on Facebook (Kahlaoui 2013).

The description of the Tunisian revolution as a Twitter or Facebook revolution served to embed a perception that the revolution was an internet creation, rather than the manifestation of the Tunisian people’s discontent with their government. This framing transmits an affirmation of a “Euro-American hand in supplying the tools of the revolt, namely the technological gadgets and all the techniques of social media” (Kahlaoui 2013, 147). This narrative was amplified by Western news media. Kahlaoui (2013) argued the Tunisian revolution was not created by the internet. Instead, the internet’s role was aggrandized by Tunisian state-controlled media to provide an alternative narrative. In this regard, social media allowed ordinary citizens to circulate a different narrative than the one advanced by mainstream Tunisian media (Howard et al. 2011; Lim 2013).

The regime was acutely aware of the threat posed by social media, particularly its capacity to provide regular citizens with the capability to easily create and circulate content. Prior to the revolution, the regime was heavy handed and strictly controlled what Tunisians could access online. Created in 1996, the Tunisian Internet Agency played the role of internet police by monitoring online content and censoring any criticism of the regime. Meanwhile, the Facebook pages of Tunisian activists were blocked while the ruling party’s regional pages proliferated. However, Tunisian cyberactivism grew when Ben Ali’s regime started a campaign of internet censorship in the late 1990s. Even during this period of strict government control social media was used as a tool of mobilization, which was evident in the anti-censorship online movements ‘Sayb Saleh' and ‘Nhara al Almar’ (Kahlaoui 2013). Further, internet activists circulated content related to the six-month-long Gafsa mining protests that occurred in 2008. During these demonstrations, protesters who complained about unfair hiring practices were arrested, tortured, and three of them were killed by security forces (Amnesty International 2018). The regime subsequently blocked Facebook in August 2008.

On January 13, 2011, Ben Ali gave a famous speech announcing the end of the online blackout. By rescinding this blackout, it allowed Tunisians to access YouTube, Facebook, and other blog sites that were formerly blocked by the regime. As a result, a shift occurred in 2011, which witnessed a rise in native Tunisian cyber-activists administering blogs, which was formerly a domain dominated by expatriates (Kahlaoui 2013).

Changes to Press Freedom after Jasmine Revolution

Following the revolution, Tunisian media turned the page on decades of state-controlled press. Spontaneous changes were made following the ouster of Ben Ali. For example, the Tunisian public television network changed its logo from ‘Tunisia 7,’ which was symbol that was strongly associated with Ben Ali’s regime. These changes consisted of eliminating red lines that formerly prevented many forms of political content, adopting transitional law texts, and attempting to reconcile with Tunisian public.

Those changes can be divided into short-term items and fundamental ones. The short-term changes concerned the number of media outlets and the diversity of the offered content. Before 2011, print media consisted of state-owned newspapers, several private newspapers that were owned by individuals with strong political connections—including family ties—to the regime, and opposition newspapers. After the revolution, the National Authority for the Reform of Information and Communication (2012) identified 228 new print publications that soon vanished due to either a precipitous decline in readership, links to Ben Ali’s regime, and/or financial difficulties (Media Ownership Monitor Tunisia n.d.). Tunisian broadcast media consisted of two public TV stations that echoed regime talking points, nine public radio stations, two private TV stations, and a few private radio stations. Almost all private media were owned by family members of the Ben Ali and Trabelsi families, which are Ben Ali’s in-laws (UNESCO 2011).

The fundamental legal changes that protect journalistic freedom have yet to be finalized. Decree Law 2011-115 covers print news media, while decree Law 2011-116 covers broadcast media and stipulated the creation of the Independent High Authority for Audiovisual Communication (HAICA), which was established in 2013. Meanwhile, a new authority was supposed to be elected by parliament in 2019 as those decree laws were supposed to be temporary. However, more than 10 years later they still have not been replaced by permanent laws. During this time, a press council was established in late 2020.

Both decrees advocated freedom of expression and freedom of press. The first chapter of decree Law 2011-115 (2011) stipulates: “The right to freedom of expression includes the freedom to circulate, publish, and receive news, opinions and ideas of any kind”. Approved by the constituent assembly in 2014, the new Tunisian Constitution codified the freedom of expression and freedom of press. Even though the World Press Freedom Index ranked Tunisia at the top of all MENA countries in 2021, it fell by one rank internationally between 2020 and 2021. Reporters Without Borders (2021) warned that political issues were endangering freedom of press, hate speech was threatening HAICA, and violence was occurring against journalists. The Tunisian Journalists Union (SNJT) registered one hundred assaults against journalists in the first five months of 2021 (SNJTe 2021). Tunisian activists, bloggers, and social media users faced prosecutions—in several cases—in military courts for online criticism of officials, the government, and its policies (Amnesty International 2020; Human Rights Watch 2019, 2020). Years after the revolution, there are still issues related to the rights of social media users. However, Tunisian activists still see the internet as an important tool of democratization (Karolak 2020).

In 2021, Tunisia’s nascent democracy and temporary free-press policies faced critical tests that elevated long-held concern pertaining to their tentativeness. President Saied reiterated that his post-July 25th rule is not a threat to freedom of the press and freedom of expression. As an example of good faith, Saied removed the head of the state-owned TV stations. This was a result of allegations that a representative of the journalists’ union (SNJTc) and an activist were briefly banned from participating in a TV show shortly after his July decision (France 24 2021). However, there are signs of a deteriorating pluralism throughout Tunisian media. In late July 2021, the Al Jazeera office was closed by police and its staff was forced to work in the garden of the SNJT building (Goldstein 2021). According to a statement by Human Rights Watch, “Saied has eroded critical checks and balances that Tunisians have erected since 2011 to bar a return to authoritarian rule” (Goldstein 2021). In early 2022, the head of the journalists’ union indicated that political parties had been banned from state TV (Amara 2022). However, no other source confirmed this statement despite favorable coverage comprising 93 percent of the time dedicated to discussing presidential decisions on National TV1 (HAICA 2021a). Saied also removed the head of the Tunisian national radio whom he appointed a few months earlier. Private radio and TV channels still host shows where guests and journalists can express viewpoints critical of the president. However, the private TV stations Nessma and Hannibal TV, as well as the radio station Al-Quran al-Kareem, were banned from broadcasting due to alleged licensing issues (Goldstein 2022). Hannibal TV resumed broadcasting shortly after negotiations with HAICA (HAICA 2021b). Although they were broadcasting illegally, Zitouna TV studios was shut down and a Zitouna talk- show host was arrested after reading a poem criticizing dictators (BBC 2021). However, the TV channel resumed airing from outside the country and the host was released a few weeks later (Thebty 2021).

Journalists’ Role Perceptions and Worlds of Journalism Survey

How journalists use social media—or avoid it—can inform role perception values identified in the Worlds of Journalism surveys. This includes a sense of professional control, importance of disseminating information, opportunity to mobilize citizen participation, or comfort with participating in news narratives rather than taking the position of neutral bystander (Hanitzsch et al. 2019). Digital tools provide individuals and journalists the capacity to instantly disseminate information via social media, rather than waiting for the presses to run. This empowerment of the individual highlights their values and amplifies role perception.

Scholarship using the Worlds of Journalism survey (Hanitzsch et al. 2019) grouped journalists across the globe into four professional roles. These roles were monitorial (watchdog), collaborative (support government efforts), interventionist (advocate for social change), and accommodative (focused on audience-centric entertainment and ‘news you can use’). Determining what roles are emphasized in a particular country is directly related to that country’s development. Journalists in countries that face disruptive changes often support an interventionalist role, while journalists in established democracies tend to ascribe to a monitorial role. The collaborative role tends to be found in locations with lower levels of democracy, while the accommodative role is present in stable and more developed societies (Hanitzsch et al. 2019). This study examined how future Tunisian journalists, who will work in an emerging free press, leverage these digital tools. Moreover, it investigates how their interactions and views of social media might inform their perceptions of their future roles.

The studies that examine journalists’ role perception and digital technologies have mostly been conducted in the U.S., Western Europe, and other established democracies. These investigations have largely been task-focused while examining how reporters use the internet as a reporting tool, fact checking tool, way to monitor the work of competitors, means of communicating with readers, venue for posting their work, or a means of finding quotes from social media (Cassidy 2005; Lasorsa, Lewis, and Holton 2012; Quandt et al. 2006). This study examined Tunisian pre-professional journalists and their use of social media and expanded upon these findings to assess their values. The assessments were based upon questions derived from research conducted by Weaver, Willnat, and Wilhoit (2019).

Pre-Professional Journalists as a Barometer

Survey participants are pre-professional journalists who produce print, online, and television news as part of their university coursework. Although they are not professional journalists, they are developing skills and habits they will take into the field, particularly as it pertains to social media. This is especially pertinent as use and values of social media are an essential part of professional role conception (Weaver, Willnat, and Wilhoit 2019). This is particularly true in a national context where social media helped enable press freedoms. Journalism students are most likely to carry their values and practices into the field, while their role perception is unlikely to change (Bjørnsen, Hovden, and Ottosen 2007). Hanna and Sanders (2007) surveyed UK journalism students and found the strongest predictor of future role conceptions was related to what motivated students to study journalism in the first place. Although journalism education plays a role in shaping how future journalists perceive their roles, scholarship has focused on established democracies (Mellado et al. 2013).

Student journalists in Tunisia have not yet been subjected to the effect of professional newsrooms as organizations that influence reporters (Shoemaker and Reese 1996), which have only operated under tenuous journalistic freedoms for less than a decade. Shoemaker and Reese’s (1996) Hierarchy of Influences model posits that individuals, routines, organizations, social institutions, and social systems affect how reporters work. Hanna and Sanders (2016) amended their model for a digitally networked public sphere. This research describes how journalists encounter influences from digital affordances at each of the five levels. Furthermore, Carpenter et al. (2015) found that upper-division journalism students are more avid users of technology when compared to lower-division students, which suggests that higher education may impact pre-professional journalistic practices.

Method

This study relied on a survey to measure the understanding of Tunisian journalism students as it relates to their professional roles, specifically as it pertains to social media. This research was conducted with the understanding these students will influence the future of journalism in Tunisia. Specifically, the study set out to answer the following research questions:

- RQ1: How do pre-professional Tunisian journalists use social media in their work?

- RQ2: How do pre-professional Tunisian journalists perceive impacts of social media on their own work and on the field?

- RQ3: How do pre-professional Tunisian journalists’ values of social media as a work tool correlate with their role perceptions?

Students at L’Institut de Presse et des Sciences de l’Information (IPSI) in Manouba, which is Tunisia’s only public higher education institution dedicated to training journalists, were invited to take the survey via email, social media, or face-to-face. A significant portion of IPSI course work involves producing journalism for print, online, and broadcast news. Data was collected in Tunisia between September 2019 and January 2020. After removing abandoned surveys, which consisted of surveys that were less than half complete, 152 respondents remained. This sample represents 29.4 percent of IPSI’s 517 students. This survey included Likert-type scale question that were utilized in previous research, which includes the Worlds of Journalism Study survey (2012) and questions used by Weaver and Willnat (2016) and Weaver, Willnat, and Wilhoit (2019). These were used to assess what types of social media respondents used in their work, how they used social media in work tasks, how they value social media as a tool, as well as how they perceive social media as an influence on their own work and on the field. The survey was determined to be exempt from review by the authors’ Institutional Review Board. It was distributed via Qualtrics survey platform with versions available in English and Arabic.

- RQ1 was informed by descriptive data from two questions. The first asked, “How often do you use the following types of social media in your work as a journalist” and measured responses using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1=never to 5= a great deal. The second asked “In what ways do you use social media? Select all that apply” and relied on binary data to assess how journalists were using social media to perform various tasks.

- RQ2 examined values and perceptions of social media as it related to the work of individual journalists, as well as on the field of journalism. It used a 5-point Likert scale, which comprised 1=Strongly Disagree, 2= Disagree, 3= Neither Agree Nor Disagree, 4=Agree, and 5=Strongly Agree. Following the method used in other WJS studies, it categorized respondents into the four WJS roles based on their responses.

- RQ3 relied on the analysis of RQ2 to assess role perceptions of pre-professional Tunisian journalists in the context of values and beliefs pertaining to social media. The eight questions from the Weaver and Willnat (2018) study used a five-point Likert scale, which is identical to the one outlined above. One-way repeated-measures ANOVA was calculated to compare the values and beliefs responses with the four different roles as the attitudes and beliefs of pre-professional journalists relating to social media may inform their future professional roles.

It is common for journalism studies to begin from a technologically deterministic perspective that asks how new technologies may impact journalism. This study intentionally focused on journalists’ agency in mutually shaping technology (Mitchelstein and Boczkowski 2009) by examining how journalists use social media to meet their goals contrasted to the way designers intended (Kline and Pinch 1996). Social media doesn’t have a singular intended use as it could be used to spread information instantly and globally, interact with others, monitor what others are saying, or for a combination of those things. Thus, all previous options map on to questions pertaining to journalistic role perception.

Since the 19th Century, scholars portrayed new electronic technologies as powerful instruments of societal and field disruption (Marvin 1990). For example, the electric lightbulb and telephone were conceptualized as tools with the ability to force changes in social norms (Marvin 1990). In the early 1990s, scholars hypothesized that television news would be the end of newspapers (Cook, Gomery, and Litchy 1992). As recently as 2012, scholars questioned whether the Internet would replace traditional news outlets (Benkler 2006; Gaskins and Jerit 2012). Similar questions are raised today as it relates to generative AI and the changes it may force upon newsrooms, which includes the possibility of replacing journalists (Miroshnichenko 2018). However, it’s important to first ascertain how journalists and news organizations will leverage generative AI as a tool. Natural Language Processing AI tools—such as spell check and grammar check—have been used in newsrooms for decades. They have accelerated proofreading, but have not replaced copy editors, nor are they always accurate. Generative AI tools, which use machine learning to mimic human-produced prose, are being positioned as a threat to journalists. However, it’s important to remember that journalists have agency over whether, and how, they leverage tools. How people use new technologies changes over time as users foreground different needs onto the tools (Leonardi 2009). For example, several years after Twitter became popular, users adopted hashtags to attract popular attention toward specific issues (Black 2018). This reveals the innate elasticity in a novel tool through user’s foregrounding their needs and goals. As those goals are closely aligned with role perception, adopting a social construction of technology approach allows for ongoing inductive exploration.

Findings

Investigating how Tunisian journalism students use and think about social media has the potential to illuminate ways that journalism might evolve in Tunisia. This is evident due to social media playing an instrumental role in organizing protests and disseminating information throughout the Jasmine Revolution. This comprehension is compounded by research conducted by Bjørnsen, Hovden, and Ottosen (2007) that indicates the professional role perception of journalism students persist after they enter the field. The study began with descriptive data to explore which social-media platforms pre-professional journalists were using, how often, and in what ways. Time has proven that social media platforms—and their associated affordances—come and go. However, it is important to investigate these platforms within the context they exist. As such, what platforms are used, and how they are leveraged, may provide insight into the values that journalism students are foregrounding onto technologies.

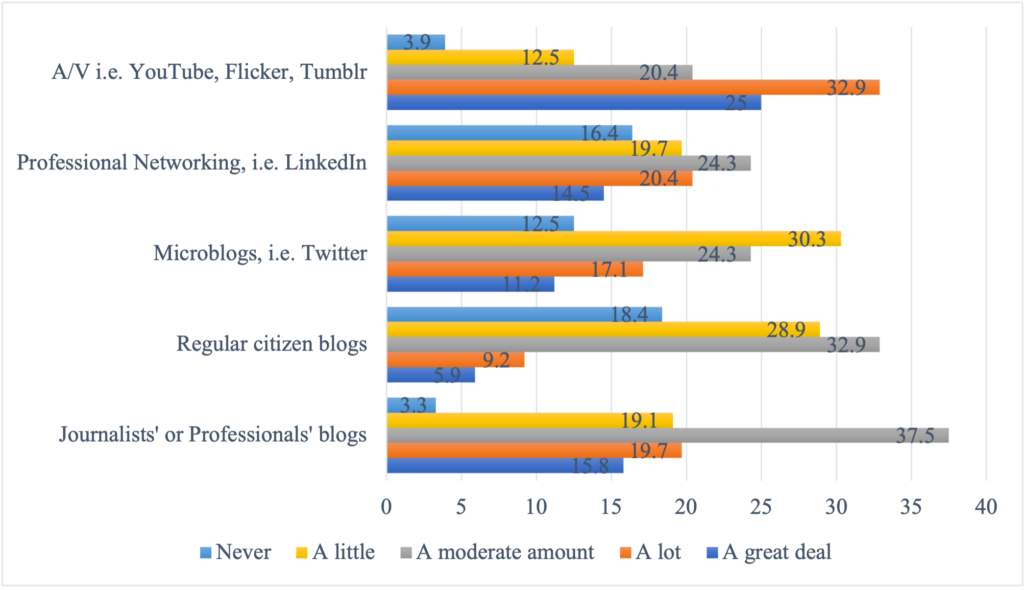

Survey results for RQ1, which asked about platforms and routines, revealed that pre-professional journalists most often use audio-visual platforms, such as YouTube and Flickr. More specifically, 78.3 percent reported using these platforms at least a moderate amount. Meanwhile, 73 percent of respondents reported accessing blogs written by other journalists or professionals at least a moderate amount, while blogs written by citizen bloggers were used the least (48 percent). Pre-professional journalists said they used social-media microblogs—such as Twitter—and professional-networking blogs—such as LinkedIn—at least a moderate amount with 52.6 percent and 59.2 percent respectively. Specific responses to RQ1 are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Pre-professional Tunisian journalists’ social-media use by type

In terms of how Tunisian pre-professional journalists are using these platforms, the survey asked thirteen questions based on the Weaver and Willnat study (2016). The responses to these questions were a mix of monitoring, information finding, interacting with the audience, checking for breaking news, keeping in touch with the audience, finding additional information, and checking what other news organizations are reporting. Each of the responses were at or above sixty percent. The least common uses involved posting and replying to comments on work-related social media, which were both below thirty percent. The responses are presented in Table 1.

| Table 1: How Tunisian Pre-Professional Journalists Use Social Media | |

| Check for breaking news | 69.70% |

| Keep in touch with my audience | 63.20% |

| Find additional information | 62.50% |

| Check what other news organizations are reporting | 61.20% |

| Find sources I would otherwise not be aware of or have access to | 58.60% |

| Find new ideas for stories | 50% |

| Verify information | 50% |

| Meet people in my field of work | 48.70% |

| Monitor discussions on social media about my field of work | 44.10% |

| Interview sources | 40.10% |

| Follow someone on social media I met in my field of work | 32.20% |

| Post comments on work-related social media | 28.90% |

| Reply to comments on work-related social media | 21.70% |

Survey data revealed pre-professional Tunisian journalists most frequently use audio-visual social media sites such as YouTube, Flickr, and Tumblr. They most frequently use social media to check for breaking news. How Tunisian pre-professional journalists self-report their routines and task-oriented work depends upon the technologies available. Moreover, their values and attitudes toward social media are strong predictors of their future roles in a digital environment.

RQ2 relied on questions based on the study conducted by Weaver, Willnat, and Wilhoit (2016) that explored how pre-professional Tunisian journalists perceive the impact of social media on their own work and on the field. The responses to these overarching questions fell mostly in the center with a slight lean toward the positive. Respondents primarily said the impact of social media on their work has been ‘somewhat positive’ (48.7 percent) or ‘neither positive nor negative’ (35.5 percent). The response to perceived impact on the profession was mostly neutral with 39.5 percent responding, ‘neither negative nor positive’. Meanwhile, 35.5 percent saying social media has a positive influence on the profession. The strongest positive reply on the 5-point Likert scale came in response to the statement, ‘Social media makes journalism more accountable to the public’ (M=3.79, sd =0.844). The strongest reply came in response to the statement, ‘Online journalism has sacrificed accuracy for speed’ (M=4.01, sd=0.96). The responses are presented in Table 2.

| Table 2: Impact of social media on the journalistic profession | |||

| N | M | sd | |

| Social media is undermining traditional journalistic values. | 143 | 3.47 | 0.948 |

| Social media makes journalism more accountable to the public. | 144 | 3.79 | 0.844 |

| Social media threatens the quality of journalism. | 144 | 3.58 | 0.979 |

| User-generated content threatens the integrity of journalism. | 139 | 3.53 | 0.887 |

| Online journalism has sacrificed accuracy for speed. | 141 | 4.01 | 0.96 |

RQ3 sought to explore whether a correlation exists between pre-professional Tunisian journalists’ perception of their professional roles and their attitudes and values regarding social media in their work. A one-way repeated-measures ANOVA was calculated using eight value questions (Weaver, Willnat, and Wilhoit 2019) for each of the four Worlds of Journalism roles (Hanitzsch et al. 2019). The analysis found a significant correlation between respondents who identified with the monitorial role and using social media to be more engaged with the audience (df=4, F=3.078, p=.018). A similar relation was found between those who identified with the monitorial role and using social media to be faster in reporting stories (df=4, F=3.461, p=.01), as well as to cover more stories (df=4, F=3.28, p=.013). For respondents who identified with the collaborative role, there was a significant correlation with using social media to promote their work (df=4, F=2.851, p=.026) and to enhance their credibility as journalists (df=4, F=3.545,p=.009). Responses from students who identified with the interventionist role significantly corresponded with using social media to be faster in reporting news stories (df=4, F=4.177, p=.003). Those who identified with the accommodative role significantly correlated with using social media to help increase their productivity (df=4, F=6.039, p=.0001) and to cover more stories (df=4, F=3.447, p=.001). Two of the values from Weaver and Willnat’s (2018) study did not correlate with any of the roles in a statistically significant measure (p>.05 across all roles). These includes, ‘Because of social media, I communicate better with people relevant to my work’ and ‘Social media has decreased my daily workload’. Four values correlated with only one role. However, the two values associated with productivity correlated with more than one role. These include ‘Social media allows me to be faster’ correlating with the monitorial and interventionist roles. Meanwhile, ‘Social media allows me to cover more news stories’ correlated with all roles except collaborative. Respondents who identified with the collaborative role did not value social media as it relates to increased productivity.

Discussion

Overall, pre-professional Tunisian journalists are adopting social media as a tool in their work and find some benefits. In some cases, the results are more tepid and vary by professional role perception. Unlike journalists in long-established Western democracies, places where journalists initially rejected and/or ignored digital interaction with the audience (Nielsen 2013; Singer 2006, 2014) have used it to amplify the voices of elites (Lasorsa, Lewis, and Holton 2012) or viewed it as an extension of the printing press (Powers 2012). Tunisian pre-professional journalists reported using social media to keep in touch with the audience and find information. Respondents viewed social media less as an extension of a one-way publishing platform and more strongly foregrounded the technological affordances of monitoring other news outlets, checking for breaking news, and interacting with the audience. These more positive perceptions of social media’s role in their work aligns with the growing use of social media in Tunisia, which boasts 8.17 million Facebook users that constitutes 68.4 percent of the population as of December 31, 2020 (Internet World Stats 2020).

The surveyed Tunisian journalism students mostly found social media to be a positive influence on their work. However, the responses were mixed as to whether it has exerted a positive influence on the profession. With the growing use of social media as a source of information in Tunisia, there is another growing challenge in the form of misinformation. Most Tunisians (91 percent) reported they encounter misinformation on Facebook (CIGI-IPSOS 2019). In Tunisia, political parties use Facebook to discredit news organizations and journalists, which may play a role in the less favorable impressions regarding the influence of social media in journalism. The positive impact of social media vis-à-vis the spread of misinformation and use by political elites to undermine journalism could explain why most students responded that it is ‘neither positive nor negative’.

Tunisian pre-professional journalists mostly do not feel that social media is a threat to their profession and are far less opposed to user-generated content than journalists in the U.S. (Weaver and Willnat 2016; Weaver, Willnat, and Wilhoit 2019, Willnat and Weaver 2018) and the U.K. (Singer and Ashman 2009). However, they also don’t feel it enhances their credibility, which could be tied to a strong perception social media is used differently by those who seek to inform versus those who spread misinformation or discredit.

In terms of role perception, journalists who identify with the monitorial role correlated most significantly with various values of using social media in their reporting. Bowe et al. (2021) found that most pre-professional journalism students identify with the monitorial role and see themselves as future watchdogs who will hold power accountable. This study provides insight regarding how they may use social media to do so. These insights include being more engaged with their audience, being faster at reporting news, and covering more stories. That first value was significant only for journalists who identified with the monitorial role. Journalists who identified with the collaborative role, which values supporting government efforts, said they use social media to promote their work and gain credibility. Journalists who identified with the interventionist role, which promotes being an advocate for social change, value social media because it helps them work faster. Journalists who identified with the accommodative role, which values audience-centric ‘news you can use’, primarily use social media as a reporting tool. In sum, there is a firm connection between these future journalists who identify with the monitorial role, which is the most popular role among Tunisian pre-professional journalists surveyed (Bowe et al. 2021). These respondents strongly value the profession as a watchdog of democracy, which includes protecting their own tentative press freedoms and valuing social media as a tool that helps engage with audiences.

Limitations and Ideas for Future Research

The questions used for this research were acquired from a U.S.-based study (Weaver and Willnat, 2016; Weaver, Willnat, and Wilhoit 2019; Willnat and Weaver 2018), which is one of the primary limitations of this research. These questions were used to assess what platforms Tunisian respondents use and for what tasks. The design of the taxonomy may have privileged how U.S. journalists perceive these platforms. Future work might benefit from more granular data collection and updating of category names such as ‘microblogs’, as well as providing more examples to render the categories more explicit.

Another limitation involves AI as this study was conducted prior to generative AI becoming widely available in newsrooms. As uses of AI technology proliferate this area is increasingly becoming a salient area of study. As such, future research questions that foreground the agency of journalists may ask how they leverage generative AI in their work.

Conclusion

The case of pre-professional Tunisian journalists forming professional identities in an emerging democracy reveals these respondents have not been exposed to the institutional norms of long-established democracies. It unveils how future journalists in Tunisia are using and foregrounding their values onto social media. This study reinforces what Allam (2019) identified in her qualitative study of professional journalists. More specifically, respondents use social media to engage with audiences and listen to their feedback, as well as speed up their reporting process to allow them to produce more stories. One interesting note, the sole measure respondents felt most negatively about involved journalists sacrificing accuracy for the sake of speed. So, while they value social media for speeding up their individual reporting processes, they concurrently feel their colleagues are not taking enough care to ensure factual reporting. Although respondents did not view social media as increasing their credibility, they also did not view it as a threat to their professionalism as identified in research involving Western democracies. Tunisian pre-professional journalists foreground social media’s capacity to provide collaboration with audiences and as a means of monitoring what other news outlets are reporting.

The fact that social media use was most strongly correlated with respondents who perceived their future professional role as monitorial is also a compelling finding. This is because the monitorial role is closely associated with established democracies as opposed to emerging ones (Hanitzsch et al. 2019). This correlation could be interpreted as future journalists believing in Tunisia’s democratic future. It points toward a confidence in the future of the field and an openness to valuing social media as a democratizing tool.

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub

Arab Media & Society The Arab Media Hub